An interview with a Shakespeare Impresario

Playing the Whole Shakespeare Canon:

Great Works and Good Work, Too

By Eric Minton

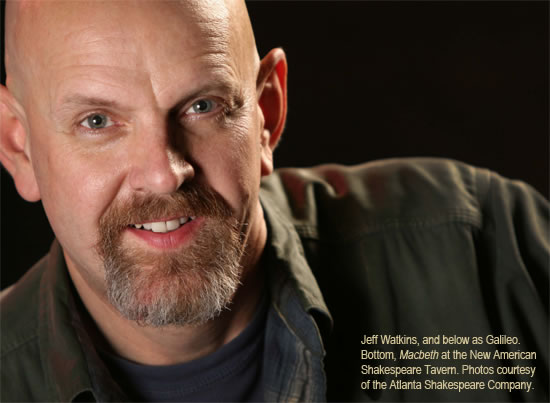

Unparalleled drama, rich characters, soaring poetry, and an efficient rehearsal schedule: Shakespeare's First Folio has it all, said Jeff Watkins, and in that collected work of plays, he has found not just good theater but a good theater business model, too. It was a lesson confirmed for him as his Atlanta Shakespeare Company this year achieved a goal of producing at its New American Shakespeare Tavern every play credibly attributed to Shakespeare.

“I think the closer we get to Shakespeare's own business model, the more successful we will be,” he said. “Shakespeare had the same actors, the same costumes, the same set, the same audience, and his job was to get those people to come back day after day after day. If you commit to his solutions, you're in good hands.”

“I think the closer we get to Shakespeare's own business model, the more successful we will be,” he said. “Shakespeare had the same actors, the same costumes, the same set, the same audience, and his job was to get those people to come back day after day after day. If you commit to his solutions, you're in good hands.”

Watkins, a trained magician and one-time street performer in New York and Chicago, is these days pursuing his desires and next dinners—literally and figuratively—as artistic director of the Atlanta Shakespeare Company and its unique Peachtree Street theater just north of downtown. The 240-seat (plus tables) Shakespeare Tavern serves up The Bard, with a bar in the back offering some 25 imported and local beers and ales, including Guinness and British ales on draught. Patrons dine on such pub grub as shepherd's pie, roasted tarragon chicken, Cornish pasties, spinach and cheese enchiladas, and various sandwiches, salads, soup, and black bean chili (traditional pub grub legitimately has a bad rep, but the Shakespeare Tavern's food is quite good, with the shepherd's pie rivaling that of an Irish pub up the street in Buckhead).

The only full-time, year-round professional acting ensemble in Georgia, the Atlanta Shakespeare Company has 21 employees—17 of whom can perform on the stage, and 14 are full-time actors and/or directors. The company also sends some of its members out to local schools for eight-week workshops that end with the students performing plays at their schools as well as at the Tavern. The company performs a wide range of classics plus 19th and 20th century works, but its bread and butter—or, rather, what brings people to eat its breads and butter—is the namesake playwright.

In staking its claim as the first U.S. company to play the entire canon of Shakespeare's plays, Watkins' enterprise staged not only all of those in the First Folio plus Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen, but also two plays of questionable Shakespearean authorship, Edward III and Double Falsehood, or The Distressed Lovers (nee Cardenio). Watkins, who founded the company in 1984 and started producing plays at the locally famous Manual's Tavern before moving to the company's own Peachtree Street digs in 1990, didn't necessarily set out to produce the whole canon of plays. As he was planning out last season, he realized the company had done 34 of Shakespeare's known plays, lacking only Coriolanus, Henry VIII, Timon of Athens, and The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Then somebody pointed out that Edward III was in the Riverside Shakespeare. Watkins was unfamiliar with it. “I start reading it out loud and I go, ‘It's Shakespeare. I have to do this,'” he said.

Watkins decided to go for broke and do all five plays in a single season, not only because he's somewhat impetuous anyway, but also as part of a long-term economic strategy. Because his theater's near-term future might require more reliance on the always-popular titles, he said, “this last year I really wanted to reach out to the übergeeks in my audience, and I really wanted to sound the horn to say, ‘We're the company that does it all.'”

In the Tavern lobby, 39 posters feature production photos of every Shakespeare play the company has done there from Pericles in 1999 through Edward III. On that last poster is written, “Commemorating the Completion of Shakespeare's Canon on March 17, 2011.”

Then somebody pointed out that the Arden Shakespeare series has published Double Falsehood, first printed and “revised” by Lewis Theobald, who claimed he started with a Shakespeare-penned play. The Royal Shakespeare Company in England also produced a version of the play this year. So, Watkins felt obligated to produce it, too, and scheduled a short run in June.

Upon reading it, he determined it was not Shakespearean. Furthermore, the director, Andrew Houchins, decided it not only was not Shakespeare, it was so bad that the only way to stage it was as an over-the-top presentation in the theatrical style of the play's actual publication date of 1727. This was a way to adhere to the company's mission of producing plays “guided by a single clarion principle that ASC reveres above all others: the voice of the playwright.” Watkins and Houchins could not hear Shakespeare's voice through Theobald's, but at least they had covered the company's canon track record.

Theobald's Double Falsehood aside, the biggest surprise Watkins discovered in completing the entire canon was not simply the unexpected hits that were King John and Two Noble Kinsmen, but how every one of Shakespeare's plays resonated with the Tavern audiences. “The playwright has never let me down,” Watkins said. “I kept expecting to get up to the clunker, the one that really had nothing to offer and there's a reason the play is never done, and I never found that.”

For Watkins, the experience proved his belief that Shakespeare's texts are all you need to produce great theater. He is not interested in conceptualized productions of Shakespeare with modern visual metaphors layered over the poetry. To him, these visual gimmicks not only denigrate the poetry itself, they ultimately rob the plays of their powerful payoffs—and as a street performer, Watkins learned early on that it is the payoff that wins over the audience and earns you that night's meal. “Actually, when I started (in 1984), I meant to let the plays teach me enough so I could monkey with them, but I've never gotten past that,” he said. “The plays keep talking to me. There's more there, even to the point where I've done the play five or six times in some cases.”

Overly conceptualized theater also robs the performance of the spontaneity Watkins deems so important, another street performer lesson he brought to his Shakespeare theater. Indeed, he feels a street performer kinship with Shakespeare and the Chamberlain's Men/Kings Men companies, who not only played to rowdy crowds in the theaters but in banquet halls, taverns, markets, and other makeshift stages. In all those settings, the actors had to interact with the audiences and, using Shakespeare's text, win them over. It was an interpersonal dynamic.

Overly conceptualized theater also robs the performance of the spontaneity Watkins deems so important, another street performer lesson he brought to his Shakespeare theater. Indeed, he feels a street performer kinship with Shakespeare and the Chamberlain's Men/Kings Men companies, who not only played to rowdy crowds in the theaters but in banquet halls, taverns, markets, and other makeshift stages. In all those settings, the actors had to interact with the audiences and, using Shakespeare's text, win them over. It was an interpersonal dynamic.

Purity of text along with an improvisational performance dynamic makes Shakespeare—all Shakespeare, as Watkins feels he has proven—not only accessible to modern audiences but to what he calls “normal people” as opposed to elitist intelligentsia. He's proud of an intended insult from the director of a rival Shakespeare theater who said of the Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern, “Anybody can enjoy that.”

Such was Shakespeare's own business model, Watkins contends, based on theaters that had no fourth wall, pre-electric standards that not only precluded special effects but also dictated the performance schedule, and the need to get return business by constantly producing fresh material that would attract “normal people.” Watkins is therefore not only trying to replicate Shakespeare's production environment with the tavern setting, but also The King's Men's business operations with a repertoire company.

Even in that, Shakespeare's texts offer valuable clues. Working through the whole canon confirmed for Watkins his theory that the act structure in the First Folio is, in fact, The King's Men's rehearsal schedule. Watkins has come to build his own rehearsal schedule on the five-act break-down. As a Shakespeare aficionado, he looks at the three Henry VI plays and sees a series so taut and trim it would be an injustice to condense them into two plays; as a theater operator, he looks at the three Henry VI plays and wonders why any producer would settle for selling two tickets when you can sell three.

Watkins freely admits he is not a scholar; he's wholly a Shakespeare practitioner. He also points out that some academics and critics consider him a charlatan. Granted, he is practiced in magic, so perhaps remembering his adeptness at sleight of hand is in order. But the company has a 27-year history operating in three successive theaters (after moving from Manual's Tavern to Peachtree Street in 1990, the theater underwent a complete, $1.6 million renovation and expansion in 2001). The company was the first American company to perform on the stage of Shakespeare's Globe in London, England. And now it is the first U.S. company to complete the canon (with people flying from England to see the Tavern's Two Noble Kinsmen and Edward III to complete their own personal Shakespeare canon). On the two nights I saw Double Falsehood, the Tavern was about 80 percent full, and about a dozen people identified themselves as first-time patrons. All of that testifies to the credibility of his practices if not his theories.

To complete my own personal Shakespeare canon, I flew from D.C. to Atlanta to see Double Falsehood (I still have not seen Edward III). I had been to many plays at the Tavern when we lived in Warner Robins, Ga., in the late '90s, but this was my first return visit since the Tavern became “New” in 2000. After seeing the play Saturday evening, a couple of hours before curtain on Sunday afternoon, June 5, 2011, I sat down with Watkins, who played various “Citizens” along with the Prologue in Double Falsehood. In an office-cum-conference room upstairs from the lobby, we talked about the Atlanta Shakespeare Company's mission and producing the entire Shakespearean canon. Our conversation began with our individual experiences enjoying the Henry VI plays, mine sitting in the audience for the American Shakespeare Center's productions at the Blackfriars Theatre in Staunton, Va., Watkins producing them downstairs in the Tavern.

October 13, 2011

[For the interview, click here] [For a PDF of this interview, click here]

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances