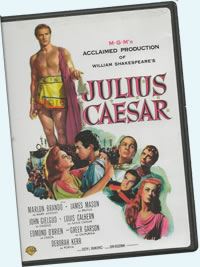

Julius Caesar

Brando in a Toga Ushers Shakespeare

Into the Modern Cinema

MGM (1953, Warner Bros. DVD, 2006)

Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. With Marlon Brando, James Mason, John Gielgud, Louis Calhern, Edmond O’Brien, Greer Garson, Deborah Kerr.

At the time this Julius Caesar was filmed, Marlon Brando was a young, hot matinee idol accustomed to tight-T-shirt-and-leather roles. Shirtless and wearing a Roman skirt to play Marc Antony was sure to get girls salivating over this bit of Shakespeare in 1953.

At the time this Julius Caesar was filmed, Marlon Brando was a young, hot matinee idol accustomed to tight-T-shirt-and-leather roles. Shirtless and wearing a Roman skirt to play Marc Antony was sure to get girls salivating over this bit of Shakespeare in 1953.

So, where does that leave us old guys in 2012? It leaves us also salivating over his performance as Marc Antony, which is enough of a reason to see this mostly palatable production of one of Shakespeare’s most plodding products.

Despite an all-star cast, the text doesn’t get much of a giddy-up in this version, but Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz still manages to make it an interesting telling of the play, especially visually. Though much of the movie was filmed on a backlot and gives us as artificial a Rome as you will ever see, it won the Academy Award for art and set decoration (in the black-and-white category) and was nominated for cinematography (black-and-white) as well as for Best Picture. Despite the elaborate set and mostly stagey action, this is not a staid theatrical production. Camera tracking and edits put you in the thick of the Roman crowds; shadows of columns and characters add to the conspiratorial feel of the movie’s first half, and the many statues seem to become additional characters. Cassius spews his “this man is now become a god” speech in the face of Caesar’s statue while the stone rendering, by its very expression, goads Cassius in return. Antony later shares a moment of conspiratorial trust with a bust of Caesar after the assassins and other political opponents have been “spotted” for death.

The movie also helps Shakespeare’s script by cutting portions of it, especially much of the last act. The war is narrowed to one battle, and about five minutes of film is absent any dialogue; just Antony on a horse preparing to give a signal. Otherwise, the script is pure Shakespeare, and it is acted in a style that is more formal speech-making than method.

That is perhaps as it should be, the argument could go, for one of Julius Caesar’s themes is the art of speech, beyond the famous scenes in the public pulpit with first Brutus and then Antony addressing the crowds after Caesar’s murder. Cassius uses carefully constructed conversation to entwine Brutus’ soul, like an agent selling adjustable-mortgage refinancing of your home. Casca and the other fringe conspirators dance around the intended meanings of their phrases. Even Brutus relies on rhetorical process in his soliloquy to convince himself to kill Caesar.

The counter argument is that formal speechmaking doesn't often make for three-dimensional characters, and that argument unfortunately holds sway in this film. James Mason is a dour Brutus, forever pouting and seeming more skittish than honorable. Such is Mason's earnestness to make Brutus a thoroughly nice guy that he seems to build his entire character on his final line spoken at the moment of his suicide: “Caesar, I killed not thee with half so good a will.” That’s obviously true from Brutus’ behavior throughout the play, but not altogether understandable because Louis Calhern is an overblown jerk as Caesar (I wrote a different noun than jerk in my notes). He is so pompous that his last speech spurning Metellus’ suit makes you urge the assassins to just get on with the killing. Please.

John Gielgud, in his U.S. film debut, is a one-note Cassius. Certainly, it’s a beautiful note coming from Gielgud, but it does not make for an engaging character. That is, until his big blow-up scene with Brutus in their army’s camp. After reconciling, the two plan war strategy with their generals, and Brutus once again overrules Cassius’ wiser council. Though Brutus is now 0-for-umpteen in important decisions, Gielgud’s Cassius accepts with resignation rather than cross Brutus again, but we also see he clearly knows that he has just accepted his death sentence. If Gielgud had given this much subtle detail to his performance up to this point we’d be devoting this essay to him.

But he was still a practitioner of the speechified-style of Shakespearean acting that was the norm in those days. That fact underlies why this production of Julius Caesar is something of a watershed film in Shakespearean cinema, for surging through the artifice is Brando, who received an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Antony. Brando may have respected the legacy of Gielgud enough that he sought out the great British thespian for some tutoring in Shakespearean acting—and subsequently, early on, he exhibits traditional Bard playing. However, he was by training a method actor, and this movie came out the same year as The Wild One.

Brando is not so much Johnny Antony, but he does give the part a swagger and natural verve lacking in any of the movie's other portrayals. A nonentity in the first few scenes, Brando's Antony approaches the conspirators after the murder as both a lightweight actor among well-versed veterans and an uncertain Caesar protegé among cold-blooded assassins. Brando and his Antony, though, both take charge of this scene as he greets and shakes the bloody hand of each conspirator; one by one his confidence grows. His subtly oily expression hints that his friendliness is feigned, and as he senses he’s on surer footing he launches into an exuberant passion over the body of Caesar. When Cassius interrupts to ascertain a commitment to the conspirators, Antony exhibits such steel-eyed bravery that Cassius is compelled to concede.

Antony’s big moment is the centerpiece speech at Caesar’s funeral, and Brando is not at first a standout in delivering these famous lines. He works through the repeated “ambition/honorable” phrases, sufficiently but with little nuance, as an actor who's been tutored by one of the great British thespians. He then pauses while his heart “in the coffin there with Caesar…come back to me”—and in that pause, back turned to the crowd, he gauges the citizen’s changing mood. When he resumes the speech, Brando does so with a Stanley Kowalski intensity and roar that, along with the camerawork, puts you right there with the now-inflamed crowd of citizens hanging on his every word, gesture, and expression. While the crowd runs riot, you share Antony’s smile.

Brando is not a great Antony, per se. But he is the great Marlon Brando, and his performance and Mankiewicz’s film work makes this entertaining Julius Caesar a worthy resident of any Shakespearean cinema library.

Eric Minton

March 15, 2012

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom